Rethinking the Hindu Temple

Tekton

Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2020

pp. 68 – 71

Rethinking the Hindu Temple

Tekton

Volume 7, Issue 1, March 2020

pp. 68 – 71

Devipriya Pillai

The extensively studied, critiqued and extolled Hindu temples have been a huge part of the architectural landscape in India. For over one and a half millennia, temples are and have always been relevant and significant in the memory of people. Today temples can be seen in every nook and alley, some retaining the grandeur and magnificence of the past and some tucked away in the niche carved by the heavy bustle of modern life. However, since antiquity, India has passed through tremendous evolution, in terms of its society, lifestyle, etc. and most importantly architecture has also contributed enormously in shaping its cultural landscape to what it is today.

With Independence, India embarked upon a quest of finding its ‘modern’. This was also reflected in architecture when many early pioneers reposed their faith in modernism as a social cause. This only got an impetus through the development of Chandigarh and architecture that followed under the influence of Le Corbusier. This move towards modernity was predicated by Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru and his proclamation of dams and industrial front as the ‘Temples of Modern India’. Ironically, in this, the actual temples didn’t really experience the wind of change. A large section of contemporary temples still remained in the shadow of the traditional temples. That is, in such temples the evocation of the past seems to take a greater significance than the relevance to the present.

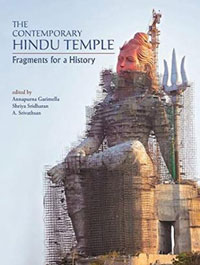

The Contemporary Hindu Temple: Fragments for a History (2019)

Editors: Annapurna Garimella, Shriya Sridharan, A. Srivathsan

Publisher: The Marg Foundation

Pages: 152

Price: INR 2800

The recently published book, The Contemporary Hindu temple: Fragments for a History, is a perusing of the modern Hindu temples. It treats the Hindu Temple as a ‘multifaceted object’ of study and questions into different aspects of it, for the reader to rethink the contemporariness of Hindu temples. And unlike the plethora of previous research on the topic, this book uses “’contemporary’ as a viewpoint to examine ancient as well as recently built temples, rather than as a unified aesthetic with overarching features.” – which opens up fresh directions and frameworks for study.

The book is a compilation of ten varied conclusions derived by different scholars in the field. It starts by an introduction by Dr. Annapurna Garimella, who sets the pace and acquaints the reader with the subject matter, for them to better understand the further essays.

The first essay in the collection, ‘Temple renovation and Chettiar patronage in colonial Madras Presidency’ by Dr. Crispin Branfoot, starts with the query – “where have all the temples gone?”, questioning the lack of studies pertaining the temples built after 18th century. The study specifically focuses on the Tamil region of southern India and the Tamil patronage. The author shines a light on the temples built and renovated in the 19th and 20th century, in accordance to the patrons who built them and their motivations. This research with its exemplifications and analysis concludes how even after colonization, the traditional Hindu Temple construction was continued throughout the centuries with the help of the Sthapatis by the patrons (wanting to be like the old kings).

The following essay, ‘Resilient monuments and robust deities: renewing the sacred landscape and making heritage sites in contemporary Bengal’ by Pika Ghosh, is an analysis of temples and the process of placemaking of these temples, by their engagement to the local communities and the liturgical renovations. Studying the temple town of Bishnupur in West Bengal, the author derives the factors like placemaking, connection to the communities, etc., which must be considered in the reconceptualization of temples today. In continuation to the previous essay, the third essay in the book, ‘Sri Govinda Dham: devotion in grievance’ by Baishali Ghosh, is a beautiful story and a perfect example of how architecture (temples in particular) can be a social adhesive. In this, the author takes us to Kanchannagar, where few refugees and the local community through all odds managed to build their haven, in the form of SGD (Sri Govinda Dham). A regular temple, which like its story moves away from the general traditional canonicals, while still retaining importance in the community’s heart over other ‘historical canons’. This research resolves the question of divinity – how divinity comes from the people, by the local connect rather than the ‘signs and the symbols’.

The fourth essay written by John Stratton Hawley, ‘Vrindavan and the drama of Keshi Ghat’ is a remembrance of the past, starting with the legend of Lord Krishna and his encounter with the ‘horse demon’ Keshi. The essay journeys through with the story of how the current scenarios and the advancement of human lifestyle is affecting Vrindavan. It also poses a question of repositioning of history – “Are the temples to be protected and remain untouched or should they be modified for the ‘betterment’ of the area and the people?” The next essay, “the contemporaneity of tradition: expansion and renovation of the Vedanta Desikar temple in Mylapore, Chennai” by Shriya Sridharan, focuses on the expansion and renovation of the Sri Vedanta Desikar temple, through which the author derives a relation between traditional and modern – “…materiality or formal language is not always as defining a factor, as art history supposes, as new materials usher in new formal languages.”

Annapurna Garimella has written the next essay, ‘Svayambhu in the Park : Temples in Jayanagar, Bangalore’, in which she takes us to Jayanagar, Bangalore. The essay mainly observes the evolution of Prasanna Ganpati Temple, which grew from a small shrine under a heritage Pipal tree to a full-fledged temple with many devotees crossing it every day. The essay, through this temple and the development of the entire street in which its rooted, goes on to explain the relevance of temples and how “…the post-independence planning regime assumed, and to a large extent imagined, the city as a place where people would want less religion, not more. But in fact, the exact reverse has happened. The city today is one of the most important sites where religion is produced and entangled with many other aspects of civic life.”

The seventh essay, ‘New Iconographies: Gods in the age of Kali’ is by Vaishnavi Ramanathan. As the title suggests, the author presents a case of iconographies and the idols being reimagined, the essay delves deeper into the reasonings and the effects of the same. The ‘Age of Kali’ – Kali Yuga – as referred by Samuel Parker in his writing on the aesthetic value of contemporary icons refers to the present time. This essay forms one of the most important and relevant study in the book as with the changing landscape and the emergence of liturgical reforms, it becomes important to appraise the icons or the deities as the ‘deities of the Kali age’ which can combat the tensions of globalization’. The observations by the author is supported by various examples like Dhanvantri Peedam, a temple founded in 2004, where the deity is wearing a stethoscope, the other fairly famous example given is of the Adhyantha Prabhu, combination of deities Ganesha and Hanuman, first illustrated by Maniam Selven. The following essay, ‘The contemporary political economy of traditional aesthetics and materiality’ by Samuel K. Parker, is a commentary on the intrusion of politics and the market into the sacral traditional arts, this is further proffered by four propositions. The author here pins on how the ‘mythopraxis’ from the ancient traditional arts is shifted to the economic culture of the modern, with the focus mainly on monetary gains than the artistic competency.

The concluding essay in the book, ‘Sacredness outside tradition? Dilemmas in designing temples’ by A. Srivathsan, focuses on the architecture and the design of the contemporary temples. It provides a case by reviewing few selected modern temples and the cognate pieces of literature. The essay points to the hesitation of contemporary architects, who end up letting historical forms dominate their imagination; by providing a juxtaposition of contemporary church architecture and Hindu temple architecture.

These essays commendably succeed in providing diverse yet pertinent facets of contemporary Hindu temple. The collection does not necessarily answer any of the question it allusively poses but instead provides the reader with enough information to start introspecting about it. The topics covered in these essays can be a predication for the reconceptualization of the Hindu temple, as what was intended. The editing and the flow of the essays successfully manages to engage till the very end. It is a very interesting and inspiring read for anyone interested in temple architecture.

Devipriya Pillai is a final year B.Arch. student at MES Pillai college of Architecture, Navi Mumbai. She is an avid reader, with a special interest in history of art and architecture. The slow ignorance of architectural progression around her, impelled her to explore the contemporaneity of modern landscape in depth. She is currently researching for her thesis about ‘contemporary temples’.

Devipriya Pillai is a final year B.Arch. student at MES Pillai college of Architecture, Navi Mumbai. She is an avid reader, with a special interest in history of art and architecture. The slow ignorance of architectural progression around her, impelled her to explore the contemporaneity of modern landscape in depth. She is currently researching for her thesis about ‘contemporary temples’.

TEKTON JOURNAL ISSUES

EDITORIAL

PAPERS & ESSAYS

Natural Ventilation as a Key Airborne Infection Control Measure for Tuberculosis Care Facilities: A Review

Raja Singh and Anil Dewan

[pp. 8 – 17]

[pp. 8 – 17]

The Changing Role of the Contemporary Public Realm: Case of Industrial Design Districts in Milan

Bhagyasshree Ramakrishna

[pp. 18 – 32]

[pp. 18 – 32]

Deconstructing the Gender in Construction Industry

Sudnya Mahimkar and Seema Shah

[pp. 34 – 45]

[pp. 34 – 45]

PRACTICE

Design Challenges in Present Day Housing: Learnings from Tara Apartments

Sanjay Kumbhare and Sushama Dhepe

[pp. 46 – 53]

[pp. 46 – 53]

Dialogue

An International Perspective of Contemporary Urban Planning

Aruna Reddi in Conversation with Ray Bromley

[pp. 54 – 66]

[pp. 54 – 66]

BOOK REVIEW

Rethinking the Hindu Temple

The Contemporary Hindu Temple: Fragments for a History, Annapurna Garimella, Shriya Sridharan, A. Srivathsan (Eds.) (2019)

Devipriya Pillai

[pp. 68 – 71]

[pp. 68 – 71]